1968

This

article appeared in the December 1968 issue of Eye

magazine,which was published by the Hearst Corporation under

the supervision of Cosmopolitan's Helen Gurley Brown.

And

God Bless Tim Buckley Too...

by

Jerry Hopkins

He

looks like a raggedy kid, so leaf-like and thin

you want to take him out and buy him a good meal. But his voice is haunted, haunting,

and his songs are like poems, dreams, stories, hallucinations. The searing Santa

Ana winds are blowing in Los Angeles, and southern California is simmering in

mid-summer heat. The thing to do is maintain, make life as comfortable as you

can for yourself, and let someone else take care of you.

|

|

Eye

was a music-oriented magazine that covered pop culture,

sports and fashion.

There were only 15 issues published between March 1968

and May 1969,

most with a bonus item inserted for the reader - posters,

record, comic book.

(Many

thanks to Sal Caputo for the correct attribution.)

|

Tim

Buckley is doing this in Sandy Koufax's Tropicana Motor Hotel, a sprawling complex

of asphalt parking slots and characterless eleven-dollar-a-day cubicles frequented

by musicians with hair. His home in Topanga Canyon is more comfortable, but he

had to get his car to the garage, and it's a drag to drive twenty-five miles from

that country hideaway into a smoggy city at 8 A.M. after singing at the Whiskey

a Go-Go until two. So Buckley moved his grin and his girlfriend and his twelve-string

Gibson into the motel for a day.

A

few miles to the north and east, in another section of Hollywood, a telephone

rings. "Hi," says Jainie Goldstein, "this is Tim Buckley's old

lady. We're at the Tropicana now." I say I'll be there in half an hour. Jainie

is the tough little lady Buckley wrote most of those songs about in his first

album, the one that carried his name as a title. He is free, white and twenty-one

and he has been roaming the country for five of those years, but Jainie makes

the calls and takes care of him. She is small, wiry, and looks more mature than

her twenty-one years. You've

got the untortured mind of a woman

he sang in 'Song for Jainie'

Who

has answered all the questions before

You've got the free-givin' ways of a

woman

Who has kicked all the heartache out the door

With

Jainie and only three or four close friends, Buckley is in

a strange limbo-land, that peculiar level of identity inhabited

by the "almost-star." He is

a star, of course, first-billed wherever he plays and earning

a star's salary

(between $2,500 and $5,000 a week--when he works). But he

is not, as they say in The Biz, ready for his own television

special yet. He hasn't had a smash record and although such

divergent groups as Hedge and Donna, and Blood, Sweat and

Tears have recorded some of his songs, no one has gone zipping

up the Billboard and Cash Box charts with one of the to give

Buckley even a secondhand hit (like Tim Hardin with If

I Were a Carpenter). And there is an unfortunate tendency

to lump Buckley with other personalities in today's "hip"

musical limelight, with the Tim Hardins and the David Blues

and the Joni Mitchells and the Leonard Cohens.

No--Tim

Buckley is on a different trip. Like Alice in Wonderland, he has stumbled into

a special rabbit hole of his own that no one else has found. And forget the thing

about success. "It's even weird talking about it," he once said. "Timmie

really is like a symbol of that generation he is in,"

says David Anderle, director of the West Coast office of Elektra records. "Timmie

is not a teacher or a prophet or a spokesman like Dylan. Timmie is a mirror of

the times. He is very close to being a painter. People like Timmie should be supported

without any conscious concern of making a return on the investment. He's chronicling

a generation of kids and their hangups." The Troubadour's Doug Weston, one

of the first club owners to hire him, adds: "He speaks of the confusion of

a young person trying to love. He says that love is what makes life worthwhile."

O

I never asked to be your mountain

I never asked to fly

Remember when you

came to me

And told me of his lies

You didn't understand my love

You

don't know why I tried

And the rain was falling on that day

And damn the

reason why His

songs have been called poems, dreams, stories, hallucinations. His imagery is

scattered and sad and fresh, like the rain he so often sings about. The words

above are from I Never Asked to Be Your Mountain. From a song called Hallucinations,

here is more Buckley rain: I

found a letter

On the day it rained

When I tore it open

There in my hands

Only

ash remained He

sings this song-cycle of love and life in a haunted, and haunting, voice, a countertenor

that rises and slides. A year ago his voice was one of the factors slowing his

career. Critics called it shrill, or walked out in the middle of a performance.

"He had a tendency to be a little mealy-mouthed," said Doug Weston.

"His diction wasn't what it should have been initially. He's changed now,

but the quality and texture remain -- the plea, the cry, the pain." His voice

is a blade of grass that bends in many ways, however variant, full of purity.

The

way this purity shows itself in performance can be unnerving. Buckley is sensitive,

totally aware of his environment at all times. Noises, the "wrong" temperature

or a restless audience can destroy him and the set will be extremely brief. But

if everything is right, he will stand in those worn wide-wale corduroys and loose

tan shirt, a wire-thin frame seeming barely able to support the huge guitar, and

sing for at least twice as long as expected. His dark eyes will narrow, and he

will weave and writhe sensually, as if possessed by his intricate melodies. He

is, in these intimate moments, precisely where he wants to be, as he says in Good-bye

and Hello I

am young

I will live

I am strong

I can give

You the strange

Seed

of day

Feel the change

Know the Way Sitting

in that small motel room on that searing California afternoon,

he talked of his early life. I wanted stories and facts and Buckley happily provided

them. He was born in Washington, D.C., lived in upstate New York, he said, and

moved when he was nine to Bell Gardens, California,

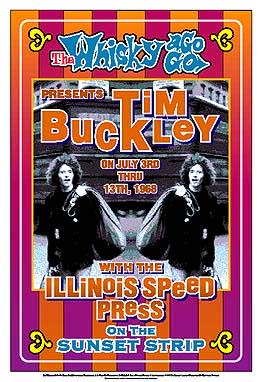

The

Whiskey A Go-Go gig referred to in this article is likely

this one; July 3-13 1968 |

settling

into a time and place that was flanked by hot rods and conservative politics and

sticky with processed pompadours. At fifteen he was a varsity quarterback, weighing

in at a less-than-impressive one hundred ten pounds. He went out for baseball

(and made the team), taught himself how to play the banjo and guitar, and baby-sat

for people who worked at nearby Disneyland. Buckley was, in Arlo Guthrie's words,

"the all-American kid." "But

I also played at car club dances with all those early Louie, Louie bands,"

he said. "You know -- carburetor soul. And getting arrested. Oh, there was

a lot of that. I hung out with the Downey Gents and the Mondo Car Club in El Monte.

I didn't have a car, so I'd go with the other guys, who were always getting busted

for rumbles and maybe stealing things." The

end of his sophomore year he decided not to play football anymore. At the same

time, he found himself becoming a troubadour. He'd been gigging occasionally with

country and western bands when they came to town, groups like Princess Ramona

and the Cherokee Riders (he says), and they'd told him stories about where they'd

played. That started him jockeying for top position on the truant officer's most-wanted

list. "They

traveled the beer-bar circuit," he said of his friends. "Oklahoma, Arkansas,

Texas, Arizona... and it sounded good, so I started traveling, too. I got busted

once or twice in Arizona and sent back home. The school got hip to me and I couldn't

even stay home when I was sick. They figured I was out with my guitar again. So

I got inventive and told them my grandmother died in New York or something. My

grandmother died several times that year. "I

really dug the people in those small towns. In Georgia they'd put you up and feed

you if you played. These people never see anybody, they never meet any performers.

I wasn't sensational. I was just doing a thing. Blues. Country. But they appreciated

it. Some day I'm gonna cut my hair and go back." (It

was during these early ramblings that he found and shed a wife. "They're

divorced now," says Herb Cohen, his manager. "It's no bad scene, but

why bring up those things -- ex-old ladies and so on. It was a long, long time

ago." Buckley still sees his ex-wife and their small son when he visits friends

in Orange County.)

During

one of his periodic visits home to Bell Gardens he ran into

a drummer named Jimmy Carl Black. They had taught music after

school in the same Santa Ana music shop and now Black was

drumming with the Mothers of Invention. He suggested Buckley

meet their manager, Herb Cohen. They met, Cohen got Buckley's

hastily formed group an audition at a local club, and Buckley

agreed to sign with him.

|