|

The

Tim Buckley Archives |

Articles |

|

Tim

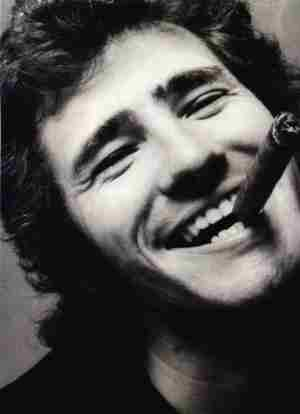

Buckley Evolved from a Hippie Minstrel to a Man Not by Leon Wieseltier It is old-folks season. The Stones and the Who and other '60s pterodactyls are back, trying with limited success to be new without not being old. What a perfect time to congratulate Enigma/Retro, a small label in Culver City, California, for having returned to the record stores almost all of the work of the most gifted singer and songwriter not to have survived the '60s (he died in 1974, along with the '60s). Tim Buckley released his first record, Goodbye and Hello, in 1967, when he was nineteen. His last record, Look at the Fool, was released posthumously, after Buckley died of drugs and booze. The nine albums that Buckley made during those seven years constitute the record of the most interesting musical and emotional maturation of that generally puerile and derivative period. Buckley began as a hippie minstrel. His early songs on Goodbye and Hello are lovely, poetically made, but they rather groan beneath the symbolism of their earnest words. Still, even on his first time out, Buckley was capable of Pleasant Street, an angry song about abjection, about edgy submission to a totemic woman: a flower of evil of the kind that Buckley would perfect with almost fearful swiftness in the short time he lived. Then the hippie vanished. In his place there appeared, on Happy Sad, a more deep and durable creature, who brooded musically upon themes beyond his years. The only record of the time comparable to Happy Sad was Astral Weeks: utterly unexpected, obviously original, almost private, looking away from rock to jazz, fascinated by the mysterious and the obscure. Where Van Morrison used harpsichord, Tim Buckley used vibes (and guitar, and bass, and congas, that was all); but in both instances the effect was one of lyrical obsession. Happy Sad was aptly named, It is a long inquiry into melancholy, now light, now dark, conceived in a philosophical frame of mind but at the beck and call of rhythm. And on this record, too, there was a sample of Buckley's rage, called Gypsy Woman, that introduced his special gift for sounding like a supremely fallen man. In 1970 Buckley released Blue Afternoon, a sophisticated collection of bluesy ballads that is almost early-twentieth-century French in its feeling of smoky languor. Then, two years later, he broke through. Greetings from LA is certainly the fiercest and most sexually exciting record that the "country culture" produced. It is an extended exercise in heterosexual fury. It is noisy, Buckley's most rockish record; it narrates without embarrassment the exploits of a man with powerful erotic longings and almost no erotic pride; it is a musical document of unrelieved and delectable pain. I know of nothing like it. It still scorches the ears. (Springsteen's Greetings from Asbury Park was a homage to Buckley's record in its title and in its design. In its music, though, it owed Buckley nothing at all.) There followed Sefronia in 1973, which has everything from The Dolphins (who remembers Fred Neil's manful, lovely song? Or Fred Neil?) to what can only be called art songs; and in 1974, Look at the Fool, the record that Buckley never lived to see, a record that is almost too subtle for its own good, the work of a man in full possession of his powers, whose standards of excellence were clearly his own. I remember Buckley well. He was a pale, wiry Baudelairean boy. He would appear on the stage, which felt only like a large table in the front, at Max's Kansas City in New York, in a Hawaiian shirt and chinos, with a twelve-string guitar. The first time I saw him was at the Bitter End, where a young duo called Hall & Oates opened for him. That was sometime in the early sixteenth century. When Buckley talked, his voice was thin. When he sang, he was a shaman. He would begin slow, but he was always building, building, building; and then, all of a sudden, the riffs on his guitar were intoxicating, perilous, huge. When he swayed with his music, when he sang the love songs of the damned, he looked possessed. You hid your wives and daughters. I confess that in the case of Tim Buckley I am completely helpless. I cannot remember my youth without him; I learned many difficult and emboldening things from him; I never expected to hear him unscratched again. Now there are CDs in the shops. There is justice. Now, if only Enigma/Retro would reissue Lorca, the one from 1970, the earthshaking record in which Buckley... (Note: The end of this piece has been lost. The Archives welcome any help in locating the missing portion.) |

|

Home • Contact us • About The Archives Unless

otherwise noted

|