|

Ode

to Tim Buckley

by

Derk Richardson

Tim

Buckley's best shot at rediscovery may have washed up on the

Memphis Harbor shore last year. That was where, on June 4,

1997, a riverboat crew found the body of his 30-year-old son,

Jeff, who had been missing for six days.

Tim

Buckley had actually been dead for nearly 22 years when the

son he barely knew went wading in the big muddy river and

drowned after being swept under the Mississippi River waters

by the wake of a large boat. But he was alive in the hearts

and minds of many.

In

the bright light surrounding Jeff Buckley's fledgling but

soaring career -- a career built on one EP, one full-length

CD, and a host of incendiary live performances -- Tim Buckley's

radical musical legacy garnered a certain amount of reconsideration.

But with the tragic demise of the son, I fear the equally

tragic but incomparably brilliant father has been cast back

into the shadowy margins of pop music history.

Why

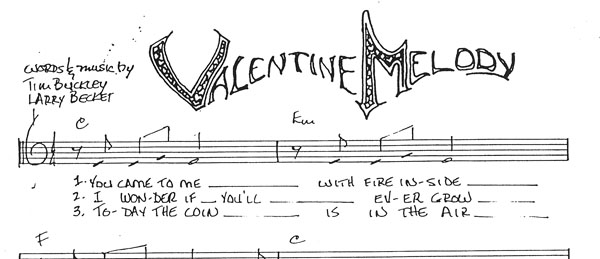

dredge him up now? Because Tim Buckley was born on Valentine's

Day, 1947, and every Valentine's Day I pull out the CD version

of Tim Buckley's 1966 eponymous debut and bathe myself in

his Valentine Melody. And because that inevitably leads

me into a listening orgy of every Buckley recording I own,

including the nine studio albums he recorded from 1966 through

1974 and the handful of live recordings that have trickled

out since his death in 1975.

Because,

despite the occasional print paean, such as Scott Isler's

July 1991 profile in Musician magazine and Martin Aston's

July 1995 story in England's Mojo, Buckley has yet to be honored

with the kind of box-set, remastered CD retrospective his

career deserves. And because I just can't pass up any opportunity

to infect others with the Buckley bug.

|

The

musical way in which Buckley channeled his emotions

and applied his voice seems every bit as revolutionary

now as it did in 1971 when he released his startling

masterpiece Starsailor. Maybe even more so...

|

Buckley's

thumbnail biography is ultimately as unenlightening as a recounting

of his less-than-blockbuster record sales. He was born in

New York and spent his adolescence in the Anaheim/Orange County

area of Southern California. Smitten with the collegiate folk

revival of early '60s, he started playing music with friends.

One connection -- drummer Jimmy Carl Black of the Mothers

of Invention -- led to another -- Herb Cohen (manager of the

Mothers, Lenny Bruce, Fred Neil, and Captain Beefheart) --

and yet another -- Jac Holzman of Elektra Records.

Well

before he turned 20, Buckley had married, dropped out of college,

fathered a child, divorced, become a coffeehouse performer,

and recorded his first albums under his Elektra contract.

As unsettled in his relationships as he was in his musical

styles, he battled constantly for both his soul and his artistic

integrity, experiencing intermittent successes and frustrating

failures in the realms of romance and self-expression before

dying of an accidental heroin-morphine-alcohol overdose on

June 19, 1975, at the age of 28.

But

the two things that mattered most were his voice and his musical

vision. Possessed of a remarkably flexible, Irish-rooted tenor,

Buckley sang with unfettered passion, extreme vulnerability,

and uncanny virtuosity. He inspired such purplish prose as

Isler's description of his singing: "His warm tenor curled

around listeners like mellow pipe smoke. Its throbbing resonance

bored into the heart with surgical precision."

Words

like "ethereal," "naive," "honest,"

and "heroic" trip off people's tongues when they

recall the way Buckley communicated with that voice. But his

most telling album title was probably the prosaic and oxymoronic

Happy Sad. As Jac Holzman noted to Isler, "To

some extent he was the bright side of people's tortured souls,

and maybe of his own tortured soul. He could express anguish

in a way that was not negative."

The

musical way in which Buckley channeled his emotions and applied

his voice seems every bit as revolutionary now as it did in

1971 when he released his startling masterpiece Starsailor.

Maybe even more so today, when the pop music idea of experimentation

is often nothing more than another technological twist on

"postmodern pastiche." Absorbing influences ranging

from Dylan and the Beatles to the electronics and avant-garde

composition of Karlheinz Stockhausen, the word-jazz of Ken

Nordine, the "sheets of sound" of John Coltrane,

and the fusions of Miles Davis and Ornette Coleman, Buckley

rapidly progressed from a psychedelic-tinged, acoustic 12-string

guitar-strumming troubadour into a shocking stylistic renegade.

He was a romantic, and he was wondrously weird.

|

As

his albums became more experimental -- from the baroque pop-rock

of Goodbye and Hello and chamber folk-jazz of Happy

Sad and Blue Afternoon through the spacier Lorca

to the shivers-inducing Starsailor -- he made his voice moan,

warble, and wail from oceanic depths to Yma Sumac-like peaks;

he toyed with song structures and tempos, brought unusual

instruments, such as vibes and pipe organ into the mix; and

he adhered to an improvisational aesthetic like few others

in pop music before or since. It's for good reason that producer

Hal Willner, who staged a Tim Buckley tribute concert at St.

Anne's Church in Brooklyn in 1991, argues that Buckley "should

be seen on the same level as Edith Piaf and Miles Davis."

Buckley

had his genre-defying peers, of course -- including Fred Neil

(whose song, Dolphins, Buckley often performed in concert

and recorded on 1974's Sefronia), Van Morrison (whose

Astral Weeks is often cited as a parallel to Buckley's

boundary-dissolving work), Laura Nyro, Nick Drake, and the

Grateful Dead. But there was/is something uniquely haunting

about the sound of his voice and his music. Maybe it stems

from his early death. Maybe it hinges on the chameleon nature

of his sound (in 1972, Buckley went for the jugular of funky

rock and roll with the torrid, lyrically lascivious, and musically

raunchy Greetings From L.A.)

Then

again, maybe it's just me. In 1975 my father described the

experience that knocked him off the wagon he'd been on for

11 years. He was walking up Sutter Street in San Francisco

when he looked into the eyes of a raggedy man shuffling towards

him on the sidewalk. He saw nothing but the most profound

sadness in those eyes. The next doorway was a bar. My father

turned in and had the drink that sent him on the most harrowing

bender of his life.

I

never saw Tim Buckley perform in concert, but in the early

1970s, I saw him walking alone on Santa Monica Blvd., not

far from the Troubadour in West Hollywood. It was a hot, bright,

clear summer day. I don't think I've ever seen a sadder looking

figure. When I listen to his music today, all that melancholy

comes rushing back, but in a way that is soul-cleansing, in

a way that exposes the human potential for joy as well as

for suffering.

And

my Valentine's Buckley binge prepares me for the spring that

is just around the corner.

Derk

Richardson

February 12, 1998

Derk

Richardson is a veteran music writer who lives in the Bay

Area

This article appeared on sfgate.com

|