|

|

May,

1985

|

Tim

Buckley -- The Interview

by Michael Davis

The

following interview took place in April 1975,

two months before Tim Buckley's death by chemical misadventure.

He had just removed himself from the cross fire between his

management firm and his record company and had an upcoming

date at the Starwood club in Hollywood, so he was eager to

talk to the press.

He

was open to discussing his entire career and some of the philosophical

underpinnings of his music, not just his then-current situation,

and came off as one of the brightest people I've talked to

in twelve years of interviewing. After his stupid, tragic

death, some spoke of him as a burnout, but this was definitely

not the case.

His Starwood show was a success, a far cry from his Bitter

End West gig a few years earlier with the Starsailor

band, where he had had to charm the waitresses out of cleaning

all the tables off so he could do a couple more tunes at the

end of the night.

He

drew a healthy crowd to the Starwood and the music was fit

as well. Older tunes like Buzzin' Fly and newer ones

like Get On Top Of Me Woman both benefited from his

quintets solid if hardly exploratory, funk-rock style and

his voice was in fine form. Backstage, Buckley told me that

plans were in the works for a live album; it was never to

be.

Listening

back to this interview tape, a chilling moment occurred at

the end when, after Buckley had mentioned Lenny Bruce several

times, I noted that Bruce had a reissue album on the charts.

The idea that Bruce could have a posthumous hit cracked Buckley

up but good.

Yet

in 1984, Rhino Records issued a Best of Tim Buckley

LP and his star is once again on the rise, particularly in

England. Ex-Teardrop Explodes leader Julian Cope has spoken

highly of him and a version of Song To The Siren (from

Starsailor) recorded by This Mortal Coil, a one-off

project featuring vocalist Elizabeth Frazer from British chart-toppers

the Cocteau Twins, has spent several weeks in the British

single charts.

Makes

you wonder if somewhere, Buckley's spirit isn't enjoying an

ironic chuckle at it all.

Goldmine:

Tell me about the management and record company changes that

are going down at this point.

Tim

Buckley: It's basically just a cleaning house. The management,

which I'm no longer involved with, has been a big problem

and that was tied in with Warner Bros. so there was bad blood

all around. I wasn't really involved with it but my music

was getting the bad end of it. My music wasn't getting promoted,

period, and since I feel really deeply about every project

I do, I hate to see 'em die like that. All I know is that

I'm free and it's great.

Goldmine:

I assume you're searching for another record company at this

point?

Tim

Buckley: Right, preferably one where one man makes the

decisions. The first record company I signed to was Elektra

and it was Jac Holzman that made it all happen. Talking to

one man is really phenomenal, knowing that something is going

to be done. When you're talking to a committee... I don't

know. There are large companies where one guy does it: Ahmet

Ertegun at Atlantic, Clive Davis at Arista, the ones that

have a genuine concern for the artist.

Goldmine:

What were your reasons for leaving Elektra in the first place?

Tim

Buckley: Jac sold the company. That was the beginning

of my problems businesswise, though I didn't know it at the

time. I knew that it was real sad and I also knew that I probably

couldn't go on at that high pitch of big business. When he

left Elektra, a huge gap opened as far as quality in the music.

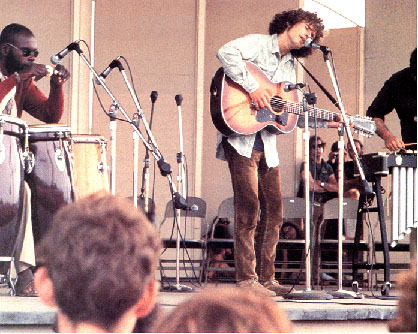

©

Elliot Landy/Landyvision.com

At the Newport Folk Festival, Newport, Rhode Island, 1968

with percussionist Carter Collins (left) and half of vibraphonist

David Friedman |

Goldmine:

Are there any musical changes going down at this point?

Tim

Buckley: Well, I'm not gonna write about record companies

and management (laughs). Musically, it's not the same as Greetings

From L.A. or Sefronia or Look At The Fool.

In a lot of ways, it's more simple but then again, more musical.

Have you ever met anyone who could successfully explain his

music at any given time? If you have, you've talked to a Top

40 artist (chuckles). I really don't know until I hear the

first tracks back.

Goldmine:

Have you done any recording towards the next project?

Tim

Buckley: Uh, no. I've written a few things that are ready

to play but I still don't know how they're going to sound.

Goldmine:

What sorts of artists were you listening to when you started

getting your music together?

Tim

Buckley: Well, I was never a folkie. I was always rooted

in African rhythms. I still listen to Duke Ellington; all those

people playing together as a quintet is just amazing to me.

That takes great writing and a great understanding of the people

in the group. I pretty much went on that principle with the

quintet; I try to understand the people that work for me as

well as he did his.

He

would write for what they were good at. If you don't do it

that way, the music just becomes a prop for the lyrics. It's

okay to .... one the same way. If you've said it once, you

should just leave it alone until you've gone through a process

where you either understand the situation better or put a

new slant on it or something.

Goldmine:

How were you exposed to these African rhythms?

Tim

Buckley: Through dance groups and people like Olatunji.

In New York, African, Latin, Puerto Rican and African things

passed through from time to time. Also, working with Carter

(C.C. Collins), my conga player.

Goldmine:

Out here, you were associated with the fabled Orange County

folk scene.

Tim

Buckley: It didn't exist. Jackson Browne was from there;

I wasn't. I just happened to play there a couple of times. I

was from New York and Washington, D.C.; when we moved here,

it was the City of Commerce, Bell Gardens. At that time, the

folk thing was really booming and the kids in the suburbs needed

guitars; it was very important to be just like the Kingston

Trio or the Limelighters.

So

I was buying up these Martin guitars at downtown L.A. pawnshops

-- the guys there didn't know what they had and some of those

Martins dated back to the '30s -- and I was running them out

to the suburbs and meeting these strange rich people who were

buying their kids guitars. Now those kids are probably lawyers

or wiretappers or whatever.

That's

how I got into Orange County. I found a few clubs that served

sassafras tea and coffee that were actual coffee houses with

no liquor so a brat of my age could play there. Before that,

I had played in country bands, lead guitar and stuff, and

I could play in bars because they didn't care.

|