|

The

Tim Buckley Archives |

| Tributes |

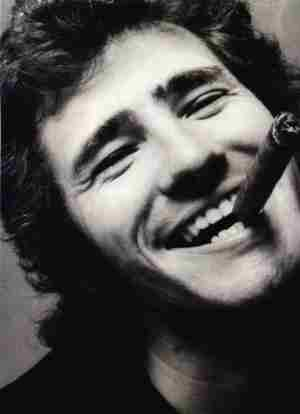

The tragic life of Tim Buckley by Tom Taylor No folk musician in history has ever slung their beat-up guitar onto the passenger seat of a Ferrari. The genre is the province of heartbroken wonderers, fingerpicking through a shit-heap of woes searching for some sort of exultation. Indeed, music is heavily regarded as a reliable engine of tragedy and misadventure, even David Bowie nearly never made it, but folk and folie is a harmonious match made in matrimony hell. Few people typify this with as much heart-strained paramountcy as one of its favourite sons, Tim Buckley. Most of the songs on his self-titled debut album released in 1966 were written when he was in high school, including ‘Grief in my Soul’. As the title suggests, it is a song of such careworn sorrow that it seems to most people that the only way he could have written it was by getting a beleaguered guardian to help out with his homework. With this inherent emotional intelligence and candid will to continually tap into it, he was lauded by Cheetah Magazine in 1965, along with fellow youngsters Jackson Browne and Steve Noonan, as one of “The Orange County Three”. With the introspective poetry and depth of Bob Dylan, but with good looks and virtuoso vocals to go with it, the trio were heralded as having the future of songwriting in their hands. Jackson Browne has rewarded the faith of the trusting critic who penned the piece with a celebrated career, Steve Noonan makes the term ‘faded into obscurity’ seem undercooked, but Tim Buckley was well on the way to making it seem like two out of three ain’t bad had he not been so tightly wound around the fickle little finger of fate. His childhood was an ordinary one, and, in 1966, at the age of just 19, he entered the world of music with his self-titled debut. He didn’t like it. It was a feet finder, with atypical period stylings and seeming conformity that the rest of his work would disavow. While Buckley himself might have been disenchanted by his first outing, it nevertheless showed enormous promise. It was at this time when the heap of his burden was added to in such a way that it would seem melodramatic if it was in a movie. Buckley’s girlfriend, Mary Guibert, fell pregnant, or so they thought, and with religious families to worry about, the pair decided to marry. In a sadly Shakespearean twist, she was not, in fact, pregnant, but soon would be just as the strains of a moot marriage began to take a toll. He left Guibert to head out into the world of music just a few months before their son, Jeff Buckley, was born. Tim would only see the future musician he had fathered less than a handful of times.

With each new record in the period that followed, Buckley slowly became an underground icon. With a searing octave range and refined cadence, he could’ve made singing the phonebook listenable, but instead, he regaled fans with gilded prose that he lovingly concocted with his co-writer, Larry Beckett. His singing could stir honey into tea from a thousand paces and while he dealt with the grief of an abandoned wife and son in a metaphysical cascade that depicted his sorrow as something profoundly spiritual. Underground, however, is the keyword here. None of his efforts were ever destined for commercial success. The fate of obscurity would befall them by design more so than any failings. His uncompromising artistry and avant-garde ways were simply a world away from the radio waves that were needed if you wanted anything other than subterranean success. He was also just about to get even more avant-garde as his collaborator, Larry Beckett, had to pack up and join the army leaving Buckley to pursue a jazzier realm inspired by forward-thinkers like Miles Davis. The albums that followed were challenging and alienated some of his fanbase. He also made the commercially disastrous decision to release Lorca, an album that teeters on the creatively berserk, alongside Starsailor a return to folky stylings almost simultaneously. Rather than an exhibit of diversity, each album diminished the success of the other. With audiences dwindling thereafter, drugs were entering the picture. He married Judy Sutcliffe in April 1970 and adopted her son Taylor. With the stability of marriage giving him strength, it would appear that Buckley cleaned up. However, the three albums that followed, Greetings from L.A., Sefronia, and Look at the Fool, took on a soul style that left many baffled and challenged a slimming fanbase even further. When he managed to sell out an 1800 seater show in Dallas, Texas, in June 1975, it was cause for celebration, but as ever, with the celestial grace that was Tim Buckley, triumph and tragedy were never far apart. He returned home to his wife that night from an afterparty in an inebriated stated. She checked on him as he lay crashed out on the sofa later that night and found he had died of a heroin overdose. As his tour manager, Bob Duffy, said in the aftermath, the death was unexpected, but it was also “like watching a movie, and that was its natural ending.” Now we are left with the beautiful realms of reverie that he crafted from his sorrow, sadly, entwined with a fate that seemed such an avoidable waste and yet an indelible part of his character and art. His music seems to somehow contain all of the above and with it, he survives. As he said himself in the stirring masterpiece ‘Once I Was’, “And sometimes I wonder, just for a while, will you ever remember me.” The song proceeds to rattle off all the things he once was and as his bandmate Lee Underwood says of Buckley’s boundless career, “[He] didn’t say, ‘I am this, I am that.’ He said, ‘I am all of these things’.” © 2021Taylor/Far Out |

|

Home • Contact us • About The Archives Unless

otherwise noted

|