| With

hindsight, Underwood traces Buckley's depressive

tendencies to his father who "suffered a head injury in

the Second World War, and from then on his insecurities and

rage made life miserable for Tim. He saw Tim's beauty, and called

him a faggot and beat him up. He looked at Tim's talent and

said he'd never make it.

His

mother didn't help : she'd tell him he'd die young because that's what poets always

did. So he grew up deeply hurt and feeling inadequate, yet driven by this extraordinary

musical talent that possessed him." The result, Underwood ventures, "gave

Tim a deep-seated fear of success...he wanted people to love him but, as they

did, he pushed them away." "Long

after his death," says Beckett, "I realized that there were very few

songs he wrote that didn't have the word 'home' in them. It seemed like he felt

homeless, and nothing would restore it. He seemed OK in high school, maybe a little

wild, but he got increasingly neurotic. He'd almost welcome a negative comment

that would reaffirm his feelings." When,

in 1970, Jerry Yester's wife Judy Henske poked fun at the line "I'm as puzzled

as the oyster" in the majestic Song To The Siren, Buckley instantly

dropped the song from the set. "He took the smallest criticism to heart,"

says Larry Beckett, "so that he couldn't even perform a song which he admitted

was one of his all-time favorites!"

Songwriting

partner and one quarter of The Bohemians - Larry Beckett at Loara High |

Another

incident stands out from this period. Tim's choirboy looks and froth of curls

had attracted a Love Generation-style teeny-bop following. At a show at New York

Philharmonic Hall, his most prestigious to date, various objects were thrown on

stage, a red carnation among them. Buckley stooped down, picked it up and proceeded

to chew the petals and spit them out. "He

was very vulnerable and emotional," says Beckett's ex-wife Manda. "It

made him terribly attractive to everybody of both sexes. People just sort of swooned

around him because he was so sweet. I think that frightened him. He was difficult

to deal with because he was scared of his power over people. He almost seemed

to reject his audiences for loving him so much. He wasn't mature enough to accept

that kind of attention." Tim

would also embroider the truth. At school he'd lie about playing C&W bars,

while Larry Beckett remembers dubious boasts of female conquests. Buckley also

claimed to have played guitar on The Byrds' first album, which Roger McGuinn always

denied. "Tim liked to feed the legend," Beckett recalls with a wry chuckle.

"He was quite amoral -- if a lie gave a laugh or strengthened his mystique,

that was fine. But his music was always honest." "If

someone dared him to do something, he'd do it," recalls British bassist Danny

Thompson, who accompanied Buckley on his 1968 UK visit. "This free spirit

was what most people saw, but I also saw a bit of a loner. Unlike most people

who get into drugs, he wasn't a sad junkie figure. He was more of a naughty boy

who said, 'OK, I'll have a go, I'll drink that.'" If

he admired Hendrix and Hardin and Havens, Buckley frequently railed against the

rock establishment. "All people see is velvet pants and long, blonde hair,"

he fumed. "A perfect person with spangles and flowered shirts -- that's vibrations

to them." "He

viewed the blues-orientated rock of the day as white thievery and emotional sham,"

says Underwood. "He criticized musicians who spent three weeks learning Clapton

licks, when Mingus had spent his whole life living his music." Retreating

to his home base in Venice, LA, Buckley and Underwood took time out to immerse

themselves in the music of the East Coast jazz titans. Miles, Coltrane, Monk,

Mingus and Ornette Coleman all provided inspiration as rehearsals slowly metamorphosed

into jam sessions. The day before playing New York's prestigious Fillmore East

theatre, Buckley asked vibraphonist David Friedman to rehearse for the show. Seven

hours without sheet music later, a new sound was born. With

Happy/Sad (1969), Buckley began to arc away from the underground culture that

had launched him. New York photographer Joe Stevens, a good friend of Buckley's

at the time, recalls the singer's suspicious attitude towards the forthcoming

Woodstock festival. "He said, 'Are you really going? Oh, man, it's going

to be awful.' Yet we used to hang out on a friend's farm which was like a scaled-down

Woodstock, with hippy girls walking around, weird food, drugs, freedom and trees."

Although

Jerry Yester was again involved, Happy/Sad was the polar opposite to Goodbye

& Hello's crowded ambition : spacious, supple, a sea of possibilities.

The line-up was just vibraphone, string bass, acoustic twelve-string, and gently

rippling electric guitar. "The Modern Jazz Quartet of Folk," enthused

vibraphonist David Friedman. "Heart music," Buckley offered, and Elektra

used his words in the ads like a manifesto. Happy/Sad's only real comparison

is Astral Weeks, a similarly symmetrical, fluid work that revels in its

lack of boundaries while possessing a unique tension. "The

trick of writing," Buckley felt, "is to make it sound like it's all

happening for the first time. So you feel it's all happening for the first time.

So you feel it's everybody's idea."

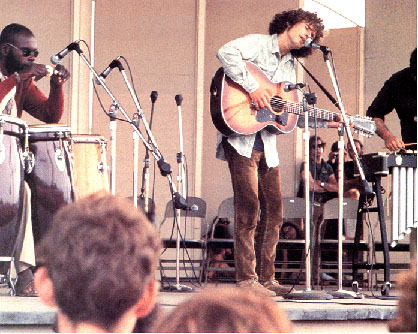

©

Elliot Landy/Landyvision.com

'The Modern Jazz Quartet of Folk' at the Newport Folk Festival, Newport, Rhode

Island, 1968 with percussionist Carter Collins (left) and half of David Friedman |

Van

Morrison, Laura Nyro and John Martyn were also melting the walls between rock,

blues, folk and jazz; at twenty-two, Buckley was the youngest of the bunch. He'd

also caught the jazz bug the hardest. Yester revealed that the band resisted second

takes, while Strange Feeling was bravely anchored to the bass line of Miles

Davis's All Blues before Buckley's voice set sail, caressing and cajoling.

"Being

with Tim was like going out with an English professor," recalls Bob Duffy,

Buckley's tour manager at the time. "He was very serious and almost stodgy,

exactly the opposite of what you'd think a rock star would be. He wasn't in the

music business to get laid. If one of the guys in the band came up and mentioned

women, thirteen of them would run out of the room, except for Tim who just sat

there, guitar in hand, almost like he was teaching himself the songs again even

though he'd played these songs two hundred times, because he wanted the show to

be as musically performed as possible. I saw incredible shows that he got depressed

about, and wouldn't talk to anyone afterwards -- he was very Zappa-like in that

demanding way, but he was one of the sanest people on that level that I worked

with." As

its very title acknowledged, despite Happy/Sad's sun-splashed backdrop,

musical invention and lyrical joie de vivre, its mood was acutely introspective.

Critic Simon Reynolds has described it as "a poignant premonition of loss,

of an inevitable autumn..." Lyrics

had clearly shifted to a secondary, supportive role. Larry Beckett says he was

politely informed that the singer would pen the lyrics alone. "He was moving

toward a jazz sound, so to have wild poetry all over the map, you'd miss the jazz.

But it was my feeling too that Tim felt his success was due to my lyrics rather

than his music, so he wanted to see how well he'd do alone. He tended to believe

the worst about himself..." "It

was very hard for me to write songs after Goodbye & Hello, because

most of the bases were touched," Buckley admitted. "That was the end

of my apprenticeship for writing songs. Whatever I wrote after that wasn't adolescent,

which means it isn't easy because you can't repeat yourself. The way Jac [Holzman]

had set it up you were supposed to move artistically, but the way the business

is you're not. You're supposed to repeat what you do, so there's a dichotomy there.

People like a certain type of thing at a certain time, and it's very hard to progress."

In another

interview Tim said, "I can see where I'm heading, and it will probably be

further and further from what people expected of me." "He

was very friendly and open to ideas, not a prima donna or a hypocrite," recalls

John Balkin, who played bass with Buckley in 1969-70. There was no drugs, sex

and rock'n'roll in relation to him as an artist, not like Joplin and Hendrix,

getting stoned before and during a gig. He felt stifled and frustrated by the

boundaries that be, trying to stretch as an artist but making a living too. I

remember Herbie Cohen saying, 'Go drive a truck then'..."

|