|

Progession

was now Buckley's watchword.

Dream Letter, recorded in 1968 at London's Queen Elizabeth

Hall, was already more diffuse than Happy/Sad, lacking the

pulse of Carter CC Collins's congas. The budget couldn't afford

him or bassist John Miller, so Pentangle's Danny Thompson

was drafted in to play an intuitively supportive -- and barely

rehearsed -- role.

"I

got a call asking me to turn up and rehearse everything at

once," recalls Thompson. "He refused to get into

a routine of singing 'the song.' We did a TV show, and when

it came to doing it live Tim said, 'Let's do another song,'

which we'd never rehearsed. It was two minutes longer than

out time slot, and the producer was putting his finger across

his throat, and Tim looked at him with a puzzled expression

and carried on, like art and music was far more important

than any of this rubbish that surrounds it. He was fearless."

Clive

Selwood, who ran the UK branch of Elektra records, recalls

the same episode : "Tim had got a slot on the Julie

Felix Show on BBC. He turned up to rehearsals with Danny

Thompson an hour late; he shuffled in, nodded when introduced

to the producer, unsheathed his guitar, and they launched

into an extemporization of one of his songs that lasted over

an hour.

The

producer and Felix watched open-mouthed, not daring to interrupt.

The most exhaustingly magical performance I have ever witnessed

-- and all to an audience of three. When it was done, Tim

slapped his guitar in the case, said 'OK?' to the producer,

and departed."

A

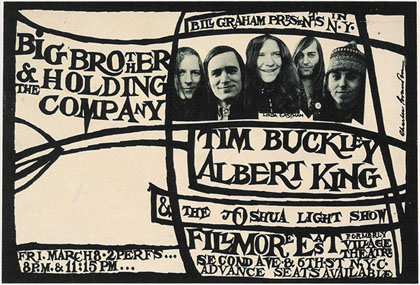

year later, after a heady bout of touring, including the Fillmore

East's opening night alongside BB King, Buckley's muse was

flying high. In 1968 he'd sounded enraptured, a wayward choirboy

testing the limits of a new-found sound, but the voice of

1969 scatted and scorched, twisting and ascending like a wreath

of smoke. The music mixed blues, jazz and ballads, throwing

in calypso, even cooking on the verge of funk. A key Buckley

moment arrived at the climax of a simmering fourteen-minute

Gypsy Woman (from Happy/Sad), when he yelled,

"Oh, cast a spell on Timmy!", like an exorcism in

reverse. Few singers craved possession so hungrily.

|

A

little-known artifact from this period is his soundtrack music

for the film Changes, directed by Hall Barlett who

later went on to helm Jonathon Livingston Seagull. A live

set from the Troubadour, finally released two years ago, previewed

material that surfaced on Lorca (1970). The album was

named after the murdered Spanish poet, whose simultaneous

violent and tender poetics Buckley was vocally mirroring.

On the song Lorca itself, and on Anonymous Proposition

and Driftin', Buckley floats and stings over a languid

blue-note haze -- crooning and stretching half-tones over

shapeless stanzas.

"We

never had any music to read from," bassist John Balkin

remembers. "We just noodled through and went for it,

just finding the right note or coming off a note and making

it right," Buckley regarded the title track as "my

identity as a unique singer, as an original voice."

The

timing wasn't great. Now tuning into such mellow songsmiths

as James Taylor, the Love Generation was in no mood to follow

in Buckley's wayward footsteps, any more than Buckley had

kowtowed to Elektra's craving for old-style troubadour charm.

As Holzman says, "he was making music for himself at

that point...which is fine, except for the problem of finding

enough people to listen to it."

"An

artist has a responsibility to know what's gone down and what's

going on in his field, not to copy but to be aware,"

the creator responded. "Only that way can he strengthen

his own perception and ability."

Around

this time Holzman was poised to sell Elektra, which upset

Buckley. Although major label offers were on the table --

"a lot of bread, which makes me feel really good"

-- he decided that money wasn't the issue : "That's not

where I'm at. I can live on a low budget."

After

some deliberation he signed to Straight, a Warners-distributed

label formed by Herb Cohen and Frank Zappa. "It would

be better for me to stay with one man who had taken care of

me," he said. "No matter what anyone thinks of Herbie,

he's a great dude." But he capitulated to Cohen's demand

to record a more accessible record : aptly named, Blue

Afternoon (1969) is a collection of narcotic folk-torch

ballads.

"Tim

always wrote about love and suffering in all their manifestations,"

says Lee Underwood. "He felt that underneath love was

fear, fear of love and success and attention and responsibility."

In the album's centrepiece, Blue Melody, Buckley keens

: "There ain't no wealth that can buy my pride/There

ain't no pain that can cleanse my soul/No, just a blue melody/Sailing

far away from me." In So Lonely, he confessed

that "Nobody comes around here no more". In press

material for the album, Buckley said the songs had been written

for Marlene Dietrich.

Blue

Afternoon beat Lorca to the shops by a month. With

two albums vying for attention, his already diminished sales

potential was halved. (Lorca didn't even chart). Buckley,

never commercially-minded, was still looking forward. "When

I did Blue Afternoon, I had just about finished writing

set songs," he told Zigzag. "I had to stretch

out a little bit...the next [album] is mostly dealing in time

signatures."

Has

any troubadour ever stretched out quite as Buckley did on

1970's Starsailor? Buckley's third album in a year,

in the words of bassist John Balkin, was ""a whole

different genre". Balkin, who ran a free improvisation

group with Buzz and Buck Gardner of the Mothers, had introduced

Buckley to opera singer Cathy Berberian's interpretations

of songs by Luciano Berio, inspiring the ever-restless Buckley

to new heights.

Over

throbbing rhythms and atonal dynamics, the Gardners' blowing

was matched by Buckley's gymnastic yodels and screams : one

moment he sounded like an autistic child, the next like Tarzan.

Everything peaked on the title song, with its sixteen tracks

of vocal overdubs. Larry Beckett, recalled to add impressionistic

poetry to expressionistic music, also had a field day : to

wit, the likes of "Behold the healing festival/complete

for an instant/the dance figure pure constellation."

Indeed.

"For

the Starsailor track itself," recalls Balkin,

"we wanted things like Timmy's voice moving and circling

the room, coming over the top like a horn section, like another

instrument, not like five separate voices. His range was incredible.

He could get down with the bass part and be up again in a

split second."

Fiercely

beautiful, Starsailor is a unique masterpiece. Aside

from Song To The Siren, the album was the epitome of

uneasy listening. "Sometimes you're writing and you know

that you're not going to fit," Buckley responded. "But

you do it because it's your heart and soul and you gotta say

it. When you play a chord, you're dating yourself...the fewer

chords you play, the less likely you are to get conditioned,

and the more you can reveal of what you are."

If

Starsailor came close to Coltrane's 'sheets of sound',

it was hard not to see it as commercial suicide. Attempts

to reproduce Starsailor live didn't help. "The

shows Tim booked himself after Starsailor were total

free improvisation, vocal gymnastics time," recalls Balkin.

"I can still see him onstage, his head down, snoring.

There was one episode of barking at the audience too. After

one show, Frank Zappa said we sounded good, and he wasn't

one who easily handed out compliments."

|