|

"Buckley

yodelling baffles audience" ran a Rolling Stone

headline. As Herb Cohen says today, "he was changing too drastically, playing

material that audiences weren't necessarily coming to hear and that was beyond

the realm of their capability" ...

"An instrumentalist can be understood doing just about anything, but people

are really geared to something coming out of the mouth being words," a resentful

Buckley said in a subsequent press release. "I use my voice as an instrument

when I'm performing live. The most shocking thing I've ever seen people come up

against, beside a performer taking off his clothes, is dealing with someone who

doesn't sing words. If I had my way, words wouldn't mean a thing." Buckley

was driven into deep depression by Starsailor's failure. Straight wouldn't

provide tour support, the old band had fragmented because there was so little

work for them, and Buckley was reduced to booking his own shows in small clubs.

At last he shared the bitter, neglected status of his jazz idols. Underwood confirms

that in order to take that sting away, Buckley dabbled in barbiturates and heroin.

When Buckley prefaced I Don't Need It To Rain on the Troubadour album by

saying, "This one's called Give Smack A Chance", it was a dangerous

joke. "He was mocking the peace movement, the whole Beatles mentality of

the day," says Underwood. At

least his personal life had improved. He'd re-married, bought a house in upmarket

Laguna Beach (subsequently painted black to outrage the neighbours), and effectively

gone to ground. "I'd been going strong since 1966 and really needed a rest,"

was Buckley's explanation. "I hadn't caught up with any living." He

also inherited his wife Judy's seven-year-old son Taylor. Judy

doesn't recall any drug abuse. Nor does she remember Tim driving a cab, chauffeuring

Sly Stone or studying ethnomusicology at UCLA, as the singer often claimed at

the time. Instead, she recalls Tim reading voraciously, catching up with his favourite

Latin American writers at the UCLA library, and channelling his creative urges

into acting.

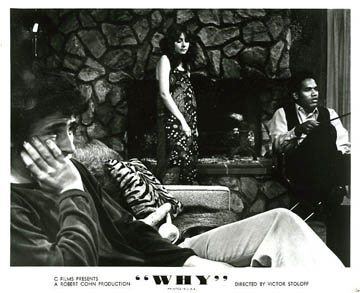

Tim,

Linda Gillen and OJ Simpson |

The

unreleased 1971 cult film Why? starring OJ Simpson was shot during this

period. "It was their first film but both Tim and OJ were incredible actors.

The camera loved them," remembers co-star Linda Gillen. "Tim had this

James Dean quality. He's so handsome in the movie and yet such a mess! You know

those Brat Pack kind of films, where people play prefabricated rebels who see

themselves as kinda bad but they have a PR taking care of business? Well, Tim

was the real deal. He didn't give a fuck how he looked or dressed. He had no hidden

agenda. He had an incredible naivety. "We

used to improvise in the film. Tim's character talks to the effect that you can't

commit suicide. You can't amend your feelings for other people; you have to find

that thing that's good in you and keep that alive. A lot of the group had been

onto my character about taking heroin but Tim would always be the sympathetic

one. But that was Tim. He'd understand where they were coming from, why they would

do what they did. "On

the set, I used to hum to myself to fight off boredom and Tim would pick up on

what I was humming, like Miss Otis Regrets, and we'd end up harmonising

together," she continues. "I loved Fred Neil, and asked if he knew Dolphins,

which he sung for me. He'd say, 'They got to Fred Neil, don't let it happen to

you.' He'd talk in this strange, paranoid, ominous way, about 'the man.' That

night, we went to buy Fred's album and bypassed Tim's on the way! He never hustled

his records to me; he wasn't a self-promoter. "I

wondered why Tim was working on this schleppy movie, because I knew people like

Roger McGuinn who were making millions, and he said, very silently, 'I need the

money.' We were only earning $420 a week on the film, and I said, Is that all

the money you have right now? and he said, 'No, I'm getting a song covered,' which

I think was Gypsy Woman, which Neil Diamond was going to do." Meanwhile,

the comedic plot of his unfilmed screenplay Fully Air-Conditioned Inside

was based on a struggling musician who blows up an audience called for old songs

and makes his escape tucked beneath the wings of a vulture, singing My Way...

When

an album finally emerged in 1972,

Buckley had once again avoided covering familiar ground. Greetings From LA

was a seriously funky amalgam of rock and soul. His youthful verve might have

gone, but his wondrous holler whipped things along. "After Starsailor,

I decided the way to come back was to be funkier than everybody," he boasted.

But would radio stations play a record as shocking lyrically as Starsailor

had been musically? Judy

was the new muse ("An exceptionally beautiful woman, provocative and witty

too," says Underwood) and the album was drenched in lust. In a year when

David Bowie made sex a refrigeratedly alien concept, Buckley wrote a set of linked

songs in a sultry New Orleans populated by a constellation of pimps, whores and

hustlers. "I went down to the meat rack tavern," was the album's opening

line; and it closed on, "I'm looking for a street corner girl/And she's gonna

beat me, whip me, spank me, make it all right again..." Buckley

explained his reasoning to Chrissie Hynde when she interviewed him for the NME

in 1974. "I realized all the sex idols in rock weren't saying anything sexy

-- no Jagger or [Jim] Morrison. Nor had I learned anything sexually from a rock

song. So I decided to make it human and not so mysterious." Producer

Hal Wilner, who subsequently organised the Tribute To Tim Buckley show at St.

Anne's Church, Brooklyn, remembers the singer at this time. "I saw Buckley

live four times, including two of the best performances I've ever seen. He was

everything someone could look for in music, totally transcendent. The first time

took 100 per cent of my attention, like taking some sort of pill. You'd expect

it from guys like Pharaoh Sanders and Sun Ra, but that's a very rare feeling to

get in rock. "Another

time he opened for Zappa in his Grand Wazoo period, and the audience was incredibly

rude to him, booing and heckling. But he handled it beautifully, just carrying

on, talking sarcastically, trying to get them to blow hot smoke on the stage.

He was genius in every sense. He should be seen on the same level as Edith Piaf

and Miles Davis." "Rock'n'roll

was meant to be body music," Buckley stated in Downbeat magazine.

But diehard fans wanted to know why he was now singing rock'n'roll. "His

last albums were dictated somewhat by business considerations," says Lee

Underwood, "but few understood they were also dictated by major music considerations.

Where else could he go after Starsailor's intellectual heights except to

its opposite, to white funk dance music, rooted in sexuality? "At

least Tim's R&B was honest, unlike the over-rehearsed stuff that pretends

to be spontaneous. Greetings is still one of he best rock'n'roll albums ever to

come down the pike. Throughout his career, he constantly asked and answered a

question that can be terrifying, which is, Where do I go from here? People criticized

him during Lorca and Starsailor and wanted him to play rock'n'roll, but when he

did they said he sold out." True

compromise was far more detectable on 1974's album Sefronia, released by

Cohen and Zappa's new DiscReet label under the Warner Brothers umbrella. "Everyone

was second-guessing where he should go next," says his old friend Donna Young,

"and Tim started listening to what other people thought." Some

new-found literary acumen was displayed on the title track, a ballad as lush as

the album's reading of Fred Neil's Dolphins. But five of the songs were

covers, including the sappy MOR duet I Know I'd Recognise Your Face, while

pale retreads of Greetings honeyed-funk served as filler. Guitarist Joe

Falsia was now in the Tonto role, Underwood having stepped down to deal with his

drug addiction. Herbie Cohen was obviously calling the shots. "Some of those

songs were beautiful, but you have to get through Herb's idea of what is commercial,"

says Underwood. As

commercial compromises go, Sefronia was terrific --

radio-friendly and lyrically approachable -- but Buckley knew the score. "If

I write too much music, it loses, as happened on Sefronia. Y'know, it gets

stale." In reference to the folk-rock era, he observed that "the comradeship

is just not there any more, and it affects the music." His boisterous barrelhouse

sound was showcased at 1974's Knebworth Festival in Britain, where Buckley opened

a bill that included Van Morrison, The Doobie Brothers and The Allman Brothers

Band. It was his first UK show since 1968, and few knew who he was. Photographer

Joe Stevens reacquainted himself with Tim at a DiscReet launch in London : "He

was sitting at a table signing autographs, which I couldn't have imagined him

doing before. When he saw me he said, 'Come on, let's get out of here,' before

they'd even said, 'Ladies'n'gentlemen, Tim Buckley!' We hit the street, took some

photos, then took a taxi back to my place. He spent two days curled around my

TV set, cooing at my girlfriend. We got calls from Warners accusing me of kidnapping

their artist! You could see what had happened to him. The youth had gone out of

his face, and his smile would break into a frown as soon as it had finished."

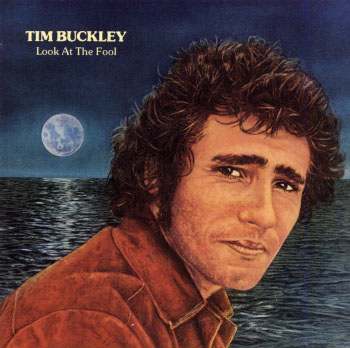

Look

At The Fool (1975), with its frazzled,

Tijuana-soul feel, was purer Buckley again, but the

songwriting meandered badly -- Wanda Lu remains one of the most ignominious

final songs of any brilliant career. "It just seemed that the more down he

became, the more desperate he sounded," his sister Kathleen told Musician

magazine. "The work of a man desperately trying to connect with an audience

that has deserted him," pronounced Melody Maker. The photo on the

back cover caught Buckley with a quizzical, defeated expression. Look at the fool,

indeed. Honest to the end.

A look at the cover

shows that Tijuana Moon was to be the name of Tim's final studio album |

In

1974, Buckley wrote to Lee Underwood : "You are what you are, you know what

you are, and there are no words for loneliness -- black, bitter, aching loneliness

that gnaws the roots of silence in the night..." "Tim

felt he'd given everything to no avail," says Underwood. "He was even

suicidal for a short while because he felt there was no place left to go, emotionally

speaking. He was gaining new audiences and improving his singing within conventional

song forms, but comments that he'd sold out made him feel terrible. He never understood

his fear of success, and remained divided and tormented to the end. I urged him

to take therapy shortly before his death, when he was feeling very bitter, to

the point of suicide, but he said, 'Lose the anger, lose the music.'" "We

saw a lot of him over the years as disillusionment set in," said Clive Selwood,

who, inspired by Buckley's session for BBC's John Peel Show, later founded the

Strange Fruit label and its Peel Sessions. "When we first met, he

spent his leisure time cycling across Venice Beach, guzzling a six-pack. When

we last met, he was carrying a gun, in fear of the reactionary side of American

life, who despised his long hair. He said, 'If you're carrying a gun, you stand

a chance.'" "He

continually took chances with his life," adds Larry Beckett. "He'd drive

like a maniac, risking accidents. For a couple of years he drank a lot and took

downers to the point where it nearly killed him, but he'd always escape. Then

he got into this romantic heroin-taking thing. Then his luck ran out." Buckley's

most revered idols were Fred Neil -- who chose anonymity rather than exploit the

success of Everybody's Talkin' -- and Miles Davis, both icons and both

junkies. "He lived on the edge, creatively and psychologically," says

Lee Underwood. "He treated drugs as tools, to feel or think things through

in more intense ways. To explore." One

planned exploration was a musical adaptation of Joseph Conrad's novel Out Of

The Islands and a screenplay of Thomas Wolfe's You Can't Go Home Again.

Of more immediate consequence, Buckley had won the part of Woody Guthrie in Hal

Ashby's film Bound For Glory. The consciousness as well as financial independence,

but in the end it went instead to David Carradine. Buckley

was still up for playing live. After a short tour culminating in a sold-out show

at an 1800-capacity venue in Dallas, the band partied on the way home, as was

customary. An inebriated Tim proceeded to his good friend Richard Keeling's house

in order to score some heroin. As

Underwood tells it, Keeling, in flagrante delicto and unwilling to be disturbed,

argued with Buckley : "Finally, in frustration, Richard put a quantity of

heroin on a mirror and thrust it at Tim, saying, 'Go ahead, take it all,' like

a challenge. As was his way, Tim sniffed the lot. Whenever he was threatened or

told what to do, he rebelled." Staggering

and lurching around the house, Buckley had to be taken home, where Judy Buckley

laid him on the floor with a pillow. She then put him to bed, thinking he would

recover; when she checked later, he'd turned an ominous shade of blue. The paramedics

were called but it was too late. Tim Buckley was dead. "I

remember Herb saying Tim had died, and we all sat there," recalls Bob Duffy,

Buckley's old tour manager. "It wasn't expected but it was like watching

a movie, and that was its natural ending." "It

was painful to listen to his records after he died," says Linda Gillen. "I

remember how vibrant he was. He had that same lost alienation as friends who had

committed suicide. He was smart, wonderful, mean, nasty, kind, racist, and a loyal

friend, all kinds of contradictions. A true original." "When

he died, I took a week off," remembers Joe Stevens. "He was special

-- an innocent in an animal machine."

In

1983, Ivo Watts-Russell of the 4AD label

had the inspired notion to marry the vaporous drama of the Cocteau Twins to Buckley's

Song To The Siren. Punk's Stalinist purge was over, and the result was

a haunting highlight of post-New Wave rock, launching both This Mortal Coil and

Buckley's posthumous reputation. Before

he died, Buckley had been planning a live LP spanning the various phases of his

career. Sixteen years later Dream Letter was released to great acclaim.

"Nobody would have listened before," reckons Herb Cohen. "Things

have their own cycle, usually close to 20 years. You have to wait." He

knowingly compromised his fierce artistic ideals, but his gut feeling was that

he'd get more freedom later," says Larry Beckett. "If he'd gone into

hiding for ten years, no end of labels would have recorded anything he wanted.

Things do come around." "He

was one of the great ballad singers of all time, up there with Mathis and Sinatra,"

believes Lee Underwood. "He would have pulled out of his youthful confusion,

expanded his musical scope to include great popular and jazz songs. Tim Buckley

didn't say, 'I am this, I am that.' He said, 'I am all of these things.'"

|